This toolkit includes information for Tribal health programs on how to implement high-quality, population-based breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screenings. Click to download the PDF version of the toolkit.

This toolkit is the result of a partnership between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Indian Heath Board (NIHB) through funding titled, “Health systems improvements to cancer screening through Tribal health systems.” With its mission of advocating for the rights of all federally recognized AI/AN Tribes through the fulfillment of the trust responsibility to deliver health and public health services, NIHB is committed to improving health and promoting health equity within Tribal communities. This includes improving access to cancer screening in Indian Country by building the capacity of Tribal health systems. It is anticipated that supporting Tribal communities to build effective and efficient health system practices will result in improved screening for cancer, specifically breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers.

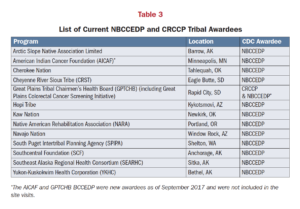

The CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Program Services Branch directly funds 13 Tribal awardees to implement health systems enhancements through cooperative agreements. This includes the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) and the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP). These initiatives aim to institutionalize priority evidencebased interventions (EBIs) found in the Guide to Community Preventive Services (The Community Guide). These EBIs are well-researched, proven strategies to increase quality cancer screening. Further information on The Community Guide can be found at https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/cancer.

This toolkit has been developed to share the best practices for programs as they implement the evidence-based interventions (EBIs) and strategies found in The Guide to Community Preventive Services (The Community Guide). This action guide is designed specifically for Tribal health systems interested in increasing high-quality, population-based breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screenings. It has been piloted with nine Tribal sites to assess overall effectiveness in implementing cancer screening EBIs.

This toolkit is composed of six primary sections: Cancer 101, Overview of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) and the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP), Overview of The Community Guide strategies, In-depth guide to implementing the EBIs in your Tribal health system, Additional lessons learned from the current NBCCEDP and CRCCP Tribal programs, and Summary — An action plan to implementing the EBIs.

This section provides an overview of The Community Guide for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers based on existing research and evidence in 2017.

This section builds on the previous one by providing an in-depth guide to implementing evidence-based strategies in your Tribal setting. It includes key steps for using the strategies in addition to resources that might be needed to ensure successful implementation. Furthermore, this section highlights the successful implementation of these strategies using “Tribal Highlights” from the current NBCCEDP and CRCCP Tribal awardees.

This section provides additional lessons learned from the Tribal awardees.

This section provides an overview of how to develop your Tribal program or clinic’s action plan to implement evidence-based strategies for cancer screening.

This section provides download links to all resources and templates referenced in other sections of the toolkit.

This section contains the following: an overview of the cancer burden in Indian Country; a primer on cancer screening tests and guidelines; an overview of the CDC’s National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program and Colorectal Cancer Control Program; a link to the American Indian Cancer Foundation’s toolkit on colorectal cancer screening; and small media examples from NIHB-funded Tribal programs.

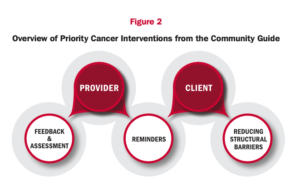

The Community Guide provides strategies to improve health outcomes by providing evidence-based interventions (EBIs) for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screenings. Issued by the Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF), these interventions are recommended on the basis of systematic reviews of effectiveness and economic evidence of what works to increase cancer screening rates. The recommended EBIs for increasing cancer screening rates are directed at both clinical providers (i.e. those referring, ordering, or administering the screening test) and clients (i.e. patients in need of screening tests). Figure 2 provides an overview of the priority strategies (provider reminders, provider assessment and feedback, client reminders, and reducing structural barriers).

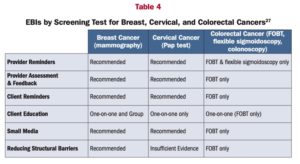

A brief description of each EBI is below, including the screening guidelines for each strategy (summarized in Table 4). Not all the screening guidelines are listed for each strategy. This means there is not enough evidence to determine whether the intervention strategy is effective. This does not mean the intervention strategy does not work; there is not enough research available or the results are too inconsistent to make a firm conclusion about the intervention strategy’s effectiveness. Programs can use interventions with insufficient evidence if they can rigorously evaluate them and publish the findings. To stay up to date on the current recommendations found in The Community Guide, visit https://www.thecommunityguide.org/.

Click to download a one-page “at a glance” guide containing all of the EBIs.

Provider reminders inform health care providers it is time for a client’s cancer screening test (called a “reminder”) or that the client is overdue for screening (called a “recall”). The reminders can be provided in different ways, either electronically using an electronic health record (EHR) system or manually in a patient’s chart.

Provider reminders are recommended for: breast cancer (mammography), cervical cancer (Pap test), and colorectal cancer (FOBT and flexible sigmoidoscopy only)

Provider assessment and feedback interventions:

Provider assessment and feedback is recommended for: breast cancer (mammography), cervical cancer (Pap test), and colorectal cancer (FOBT only).

A client reminder can either be a written or telephone message advising an individual that they are due for a screening test.

Client reminders are recommended for: breast cancer (mammography), cervical cancer (Pap test), and colorectal cancer (FOBT only).

Structural barriers are burdens or obstacles that make it difficult for people to access cancer screening. This strategy implements interventions designed to reduce these barriers and facilitate access to cancer screening services.

Reducing structural barriers is recommended for: breast cancer (mammography) and colorectal cancer (FOBT only). Evidence is insufficient to determine the effectiveness of the intervention in increasing screening for cervical cancer (Pap test).

Client education delivers information with the goal of informing, encouraging, and motivating to seek recommended screening. Client education can be delivered through the use of small media including videos and printed materials such as letters, brochures, and newsletters. Client education can occur in a one-on-one or group setting.

One-on-one education is recommended for: breast cancer (mammography), cervical cancer (Pap test), and colorectal cancer (FOBT only).

Group education is recommended for: breast cancer (mammography). Evidence is insufficient to determine the effectiveness of the intervention in increasing screening for cervical cancer (Pap test) and colorectal cancer (FOBT, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy).

The use of small media is recommended for: breast cancer (mammography), cervical cancer (Pap test), and colorectal cancer (FOBT only).

Each section below provides an in-depth look at how to use the EBIs within your Tribal clinic or program. Each section includes the following:

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Provider reminder and recall systems are evidence-based interventions to increase screening for breast cancer (mammography), cervical cancer (Pap test), and colorectal cancer (FOBT and flexible sigmoidoscopy). Reminders inform health care providers it is time for a client’s cancer screening test (called a “reminder”) or that the client is overdue for screening (called a “recall”). The goal of provider reminders is to increase delivery of appropriate cancer screening services by healthcare providers.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Provider assessment and feedback interventions are evidence-based strategies to increase screening for breast cancer (mammography), cervical cancer (Pap test), and colorectal cancer (FOBT only). Provider assessment and feedback interventions do both of the following:

Assessment — This strategy involves evaluating provider performance in delivering or offering screening to clients.

Feedback — This strategy involves presenting providers with information about their performance in providing screening services. Feedback may be done on a group basis (e.g. average performance for a group of providers) or on an individual basis with a single provider. Both group and individual performance may be compared with a goal or standard.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Sending client reminders to patients is an evidence-based strategy to increase screening rates for breast cancer (mammography), cervical cancer (Pap test), and colorectal cancer (FOBT only). A client reminder can either be a written or telephone message advising an individual that they are due for a screening test. Client reminders may include:

Initial client reminders may be enhanced by a follow-up reminder in print or by telephone, which may have one or more of the following:

In addition, the initial or follow-up reminder can be untailored or tailored.

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

Reducing structural barriers is an evidence-based strategy to increase screening for breast cancer (mammography) and colorectal cancer (FOBT only). Evidence is insufficient to determine the effectiveness of the intervention in increasing screening for cervical cancer (Pap test). Structural barriers are non-economic burdens or obstacles that make it difficult for people to access cancer screening. Interventions designed to reduce these barriers may facilitate access to cancer screening services by:

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

One-on-one education is an evidence-based strategy to increase screening for breast cancer (mammography), cervical cancer (Pap test), and colorectal cancer (FOBT only). One-on-one education delivers information to individuals about indications for, benefits of, and ways to overcome barriers to cancer screening with the goal of informing, encouraging, and motivating them to seek recommended screening. Group education is an evidence-based strategy to increase screening for breast cancer (mammography) only.

Group education conveys information consistent with that shared during one-on-one education but is usually conducted by health professionals or by trained lay people who use presentations or other teaching aids in a lecture or interactive format. This type of education often incorporates role modeling or other methods. Group education can be given to a variety of groups, in different settings, and by different types of educators with different backgrounds and styles including healthcare workers or other health professionals, lay health advisors, or volunteers. The education sessions can be conducted by telephone or in person in medical, community, worksite, or household settings.

The use of small media is an evidence-based strategy to increase screening rates for breast cancer (mammography), cervical cancer (Pap test), and colorectal cancer (FOBT only). Small media include videos and printed materials such as letters, brochures, and newsletters. These materials can be used to inform and motivate people to be screened for cancer. They can provide information tailored to specific individuals or targeted to general audiences.

This section highlights NBCCEDP Tribal Awardees that share their best practices for the holistic integration of other prevention programs that benefit their patients. A case study for one CRCCP tribal program is also included.

The Southeast Alaska Regional Health Consortium (SEARHC) BCCEDP has made linkages with two additional programs at SEARHC, the CDC-funded WISEWOMAN (Well-Integrated Screening and Evaluation for WOMen Across the Nation) program and IHS-funded Special Diabetes Program for Indians (SDPI). The WISEWOMAN program works with low-income, uninsured and underinsured women, a population shared with the BCCEDP. SEARHC has made an effort to take a holistic approach wherein recipients of the programs experience them as integrated, preventive programs. For example, this may mean that BCCEDP pays to fly women into clinics for cancer screening, but then utilizes SDPI funding for diabetes and pre-diabetes services. They also promote integration during mobile mammography clinics with WISEWOMAN/Women’s Health staff by holding WISEWOMAN events during evening hours (community fitness walks, community education talk on stress control, etc.) as well as enrolling/coaching/following up with WISEWOMAN participants when they present for mobile mammography. Furthermore, there is cross-referral between programs and patient navigators are also paid 50/50 by WISEWOMAN and NBCCEDP.

High provider turnover is an issue facing many Tribal clinics and can pose a barrier to successful cancer screening program implementation. To help alleviate the effects of provider turnover, Kaw Nation BCCEDP has a pink, laminated card placed at clinics’ reception so that staff, regardless of how new they may be, are aware of the key Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Program requirements. This helps to inform staff who may have not yet had a formal introduction to the program.

Another common issue facing many Tribal clinics is the incidence of missed screening appointments or high “no-show” rates. Missed screening appointments can be a financial burden to the clinic and potentially affect patient care as staff time is not used efficiently. They also have a damaging effect on efforts to improve cancer screening rates. To ameliorate the effects missed screening appointments may have on screening rates, CRST BCCEDP practices opportunistic screenings. This means that if a patient is in the clinic for a particular reason, program staff assess to see if the patient is due and, while they are there, the patient is offered additional screening tests that are due. Opportunistic screenings can bypass scheduling appointments, minimizing the risk for missed appointments.

Health fairs are community events where organizations come together to disseminate health information with the public and/or to provide health screenings. These community events often offer education on various health topics and are hosted by both health professionals and lay people. While they are a popular method for conducting community-based health promotion activities and offering health education, the evidence base behind them is limited. However, health fairs can be an evidence-based activity when screening tests are performed onsite or onsite scheduling of screening test appointments occur. Encounters which result in screening should be documented.

For Tribal communities, health fairs can be a critical community engagement opportunity to implement EBIs such as one-on-one education or touchpoints to coordinate group education. This includes building capacity for communities to provide education engagement with hard to reach populations. In addition to providing women with educational materials, health fairs can be an opportunity to publicize available services through culturally relevant methods. For example, Southcentral Foundation NBCCED frequently holds ‘beading circles’ at various health fairs. These beading circles are an opportunity for women to work on a beading project while also learning information about breast cancer and mammograms, typically from a breast cancer survivor. The goal is to create a welcoming environment so that women want to learn more about mammograms and have a safe place for asking questions.

The Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Health Board (GPTCHB) serves 20 facilities and 17 Tribes in South Dakota, North Dakota, Nebraska, and Iowa. Their cancer screening work focused on colorectal cancer, however they were notified during summer 2017 that they were awarded NBCCEDP funding to expand breast and cervical cancer screening initiatives.

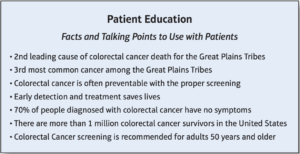

Patient education is an excellent example of the Community Guide work occurring at GPTCHB. Most patient education occurs on a one-on-one basis at GPTCHB and is typically presented by CHRs, patient navigators, subawardees including public health nursing providers, and even community champions (patients). However, they are exploring expanding their group education by using health educators and webinars and have already partnered with state health departments and with the American Cancer Society.

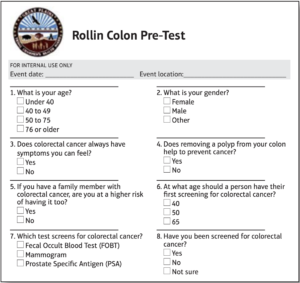

Health fairs are used as opportunities to provide onsite screenings and schedule screening appointments. For onsite screenings, GPTCHB uses “poop on demand” testing to obtain and analyze stool samples. Their FluFIT program also provides Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) lab work to eligible patients who are receiving influenza vaccines. These tests can be used at home and mailed back for testing. The Rollin Colon, pictured below, is an inflatable, walk-through colon also used at health fairs to educate patients in a hands-on way, attract interest and curiosity, and reduce squeamishness about the topic.

GPTCHB provides pre- and post-tests for patients participating in Rollin Colon activities to evaluate the effectiveness of this form of patient education.

To teach patients about colon cancer and the importance of cancer screening, GPTCHB also distributes small media including fact sheets, posters, brochures, infographics, and social media posts. Some materials are mailed to facilities for distribution, and radio ads and videos on Good Health TV are played on televisions in waiting rooms at IHS facilities. To ensure that materials are up to date, GPTCHB reviews the materials annually and revises as needed. They also work with their communications department to ensure that materials are culturally and linguistically appropriate.

Pre-test used during Rollin Colon patient education encounters.

List of talking points used for providers educating patients at FluFIT.

Although breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers pose a threat to many Tribal communities, the burden of cancer mortality can be lessened through routine, high quality screening. The EBIs found in the Community Guide are recommended on the basis of systematic reviews of effectiveness and economic evidence to reveal what works to increase cancer screening rates. This toolkit provides an in-depth guide to develop an action plan and assist your program or clinic in implementing the EBIs. Use the steps below to help your program or clinic develop its action plan to implement the EBIs.

For more information and the latest updates on the CDC’s federal programs for cancer prevention and control, visit https:/www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/about/index.htm.

This section contains download links to resources and templates found within the toolkit.

| File | Description |

|---|---|

| Implementation Plan Worksheet | This worksheet is designed to help identify the specific tasks needed, resource needs, and allocation of responsibilities to implement your chosen strategy. |

| Assess Your Progress Worksheet | This worksheet is designed to track activities and assess progress in the implementation of your chosen strategy. |

| At a Glance - The Community Guide | The Community Guide contains evidence-based interventions (EBIs) which are well-researched, proven strategies for what works to increase quality cancer screening. This one-pager provides a quick overview of the strategies. |

| CDC Screen Out Cancer Page EBI Guides | Using evidence-based interventions (EBIs) can boost your screening rates, reduce costs, and improve the quality of the care your system provides. These CDC ScreenOutCancer guides provide an overview of key considerations for implementing each strategy. |

| Examples of Program Materials |

|

| Blank Templates | Templates for the following:

|

| Additional Resources | Links to additional resources. |

| References | List of all references used throughout the toolkit. |

This section contains the following: an overview of the cancer burden in Indian Country; a primer on cancer screening tests and guidelines; an overview of the CDC’s National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program and Colorectal Cancer Control Program; a link to the American Indian Cancer Foundation’s toolkit on colorectal cancer screening; and small media examples from NIHB-funded Tribal programs.

Below is an overview of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers by describing the cancer burden in Indian Country along with screening tests and recommended guidelines for routine testing issued by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of death among American Indian/ Alaska Native (AI/AN) women (CDC 2017). Although AI/AN women have a lower breast cancer incidence rate compared to White women, AI/AN women are more likely to be diagnosed at a younger age and after their cancer has progressed to more advanced stages. Rates of breast cancer are not uniform across Indian Country, but vary by region. For example, mortality rates among AI/AN women in the Pacific Coast, Southwest and Eastern regions seem to be lower than rates for White women. However, a closer look at mortality rates stratified by age groups reveals that AI/AN women aged 40-49 years in the Alaska region and women aged 65 years or older in the Southern Plains experienced higher breast cancer mortality rates than White women in the same age group (White, A., Richardson, L. C., Li, C., Ekwueme, D. U., & Kaur, J. S. 2014). Many of these deaths could be prevented with routine cancer screening, particularly since overall breast cancer screening rates among AI/ AN women are lower (71.6%) than the screening rates for White women (76.7%) (Ibid). Similar to rates for breast cancer screening also varies by region. According to data estimates from the 2000 to 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the Southwest region had the lowest screening rates (61.1%) while the Southern Plains region had the highest screening rates (73.6%), which is still lower than the national average screening rate for White women (CDC 2012).

Cervical cancer, once known as the most common causes of cancer deaths for American women, has decreased by 50% in the past 40 years due to the increased use of the Pap test for cancer screening (American Cancer Society 2016). Although rates for cervical cancer have decreased dramatically nationally, health disparities are affecting AI/AN women in significant ways. The cervical cancer mortality rate for AI/AN women in Indian Health Service (IHS) Contract Health Service Delivery Area (CHSDA) counties is almost twice the rate in White women (4.2 per 100,000, compared to 2.0 per 100,000) (Watson, M., Benard, V., Thomas, C., Brayboy, A., Paisano, R., & Becker, T. 2014). Despite existing screening efforts, AI/AN women experienced a higher incidence rate and diagnosis at more advanced stages of cervical cancer (Ibid).

Colorectal cancer is another treatable cancer with preventive screening tests and ranks in the top five most common cancers diagnosed in the United States. Overall, colorectal cancer mortality rates have declined due to the use of screening measures such as colonoscopies, fecal immunochemical tests (FIT), and fecal occult blood testing (FOBT). Unfortunately, AI/AN people still face colorectal cancer disparities in many regions throughout the United States. For example, colorectal cancer incidence and mortality among AI/ANs have been found to be 21% and 39%, respectively, higher than White populations. Once again, these rates vary by region, with the highest incidence rates and mortality rates among AI/AN populations in Alaska and the Northern and Southern Plains regions. Additionally, indigenous people are diagnosed with colorectal cancer at younger ages and at more advanced stages of cancer, leading to a greater burden of disease. These disparities are evident in the Eastern region as well, where AI/AN women had significantly higher colorectal mortality rates than White women.

By increasing cancer screening rates per national guidelines, many cancer deaths could be avoided. Routine patient cancer screening, such as mammograms, Pap tests, and colonoscopies, are particularly effective as they can frequently prevent or detect these cancers before a person develops any symptoms.13 Identifying abnormal tissues before disease develops or discovering cancer during early stages may make it easier for the cancer to be prevented, treated, or cured, reducing morbidity and mortality and the overall burden of disease. Cancer screening is low-risk and typically causes patients only minor discomfort or inconvenience while providing valuable results.

As we work to increase cancer screening, it’s important to identify barriers such as lack of reliable access to healthcare, cultural differences, and other social determinants of health.

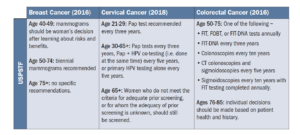

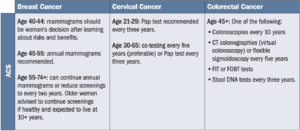

Cancer screening, which is checking for cancer or abnormal tissues before symptoms develop, is an effective way to prevent cancer or ensure early detection increasing the likelihood that a patient can be treated effectively. Cancer screening is especially important for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has national recommended guidelines for screening, which are included below and summarized in Table 1.

For additional reference, the American Cancer Society’s (ACS) screening tests recommendations for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers for people of average risk can be found in Table 2:

Screening guidelines for breast cancer

A mammogram is used to screen women for breast cancer using X-ray images of the breast. To have a mammogram, a woman stands in front of a machine that compresses her breast while an image is taken. Mammograms may feel uncomfortable or even painful. After the test is complete, radiologists read the mammograms to determine if they are normal or abnormal. Abnormal mammograms do not necessarily indicate cancer, but rather highlight the need for additional testing to look for cancer.

As of 2018, the USPSTF recommends breast cancer screening biennially for women age 50 to 74, with no specific recommendations for women age 75 and over. Women age 40 to 49 should make an individual decision to screen. There are additional recommendations for women with high risk of breast cancer, including breast MRI. Also, women should discuss family history of breast cancer and genetic testing with their provider. If screening women 40 to 49 years of age, your program must consider weighing the risks and benefits. For NBCCEDP grantees, the CDC minimum data elements (MDEs) permit a small percentage of women to be screened outside of the ages 50-74.

Screening guidelines for cervical cancer

Two tests can be used for cervical cancer prevention. The Pap test, or Pap smear, is an exam used to check for changes to the cells of the cervix that can become cancerous if not treated. The HPV (human papillomavirus) test can look for the virus that may cause changes to cervical cells. To have a Pap test, a woman will recline on a table while a healthcare provider uses a speculum tool to widen the vagina. The provider will examine the woman’s body and will collect samples from on and around the cervix. Some people may also have the HPV test in addition to the Pap test. For these patients, cells from the same sample will be tested for HPV in a lab.

As of 2018, the USPSTF recommends screening women for cervical cancer every three years beginning at the age of 21 years and continuing to age 65. Women age 21 to 29 should have Pap testing every three years. HPV co-testing is not recommended for women under 30. The USPSTF recommends Pap testing every three years, co-testing every five years, or primary HPV testing every 5 years for women ages 30 to 65. They also generally recommend ending testing at 65 years for women with an adequate screening history (i.e. three consecutive negative cytology results or two consecutive negative co-testing results within 10 years, with the most recent test occurring within 5 years before stopping screening). Testing may be advised depending on the woman’s screening history and health status. Women with a high risk of cervical cancer may need to be screened more often and should follow their providers recommendations. Women within the age range of 21 to 65 should get regular Pap tests even if they are not sexually active.

Screening guidelines for colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer normally develops from polyp growths within the colon or rectum. There are several types of screening tests that can be used to detect polyps or cancer. Stool tests include the guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (FOBT), the fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and the FIT-DNA test that are used to look for blood or cancer cells in the stool.22 A sigmoidoscopy test involves a health provider inserting a small tube into the rectum that can check for polyps or cancer in the rectum and lower colon. A colonoscopy is a similar exam, but is able to examine the entire colon and may also be able to remove polyps and cancer. A computed tomography (CT) colonography, or virtual colonoscopy, uses radiologic images and technology to display images of the colon.

As of 2016, the USPSTF recommends beginning colorectal cancer screening at age 50 and continuing through age 75.24 From ages 76 through 85, individual decisions should be made based on the patient’s health status and screening history. The FOBT, FIT, and FIT-DNA tests are recommended annually, although FIT-DNA can also be offered every three years. Colonoscopies are recommended every ten years, with CT colonoscopies and sigmoidoscopies recommended every five years. Alternatively, sigmoidoscopies can be recommended every ten years with FIT testing completed annually.

Staying up-to-date on screening guidelines

Cancer screening guidelines may change as new evidence emerges regarding the tests’ effectiveness for detection and preventing cancer mortality. For the USPSTF guidelines, programs and clinical providers can use the Electronic Preventive Services Selector (ePSS) to stay up to date. This application can be used online or downloaded to a mobile device so that USPSTF recommendations are easily accessible.

CDC is currently working with 13 Tribal awardees to improve access to cancer screening in Tribal communities through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) and the Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) within the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. An overview of these programs follows.

National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP)

Through passage of the Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Prevention Act of 1990, CDC created the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), a program providing low-income, uninsured, and underserved women access to timely breast and cervical cancer screening and diagnostic services. Currently, the NBCCEDP funds all 50 states, the District of Columbia, six U.S. territories, and 13 AI/ AN Tribal programs to provide screening services for breast and cervical cancer.

Following the passage of the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act in 2000, states can offer women who are diagnosed with cancer in the NBCCEDP access to treatment through Medicaid. The following year, passage of the Native American Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Technical Amendment Act clarified that this option also applies to AIs/ANs who are eligible for health services provided by the Indian Health Service or by a Tribal organization.

Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP)

The CDC’s Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP) aims to increase colorectal cancer screening rates among people between 50 and 75 years of age by:

The CRCC initially started as a demonstration program providing colorectal cancer screening from 2005 to 2009 to low-income, uninsured or underinsured men and women. CRCCP currently funds 23 states, six universities, and one Tribal organization.

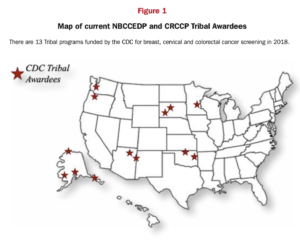

This toolkit was developed in partnership with the current NBCCEDP and CRCCP Tribal awardees (listed in Table 3 below) to improve implementation of The Community Guide strategies to improve cancer outcomes in Indian Country. Site visits were conducted to those awardees between June and September 2017 to assess implementation of the Community Guide Strategies. These programs provided crucial insight into how the strategies are used in a diverse array of Tribal settings across the US (see Figure 1 below for a map of Tribal awardee locations) including rural communities, urban communities, IHS-direct service clinics, and 638 contracted clinics.

Key takeaways from these site visits are captured in the “Tribal Highlights” found in the next section, as well as in Section 6 on “Additional Lessons Learned from Tribal Programs.”

Click here to download the American Indian Cancer Foundation’s toolkit, developed in partnership with NIHB, on colorectal cancer screening.

| File | Description |

|---|---|

| Full Toolkit: A Guide to Cancer Screenings in Indian Country (PDF) | This is the PDF version of the digital toolkit. It includes information for Tribal health programs on how to implement high-quality, population-based breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screenings. |